Bernard W. NAYOVITZ

1st Lieutenant, US ARMY AIR FORCES

Service: # O-409814

331st Bomber Squadron, 94th Bomber Group, Heavy

Entered service: 1940

Hometown: Brooklyn, New York

Born: 18 June 1917

Died: 17-August-43 in Lummen, Belgium

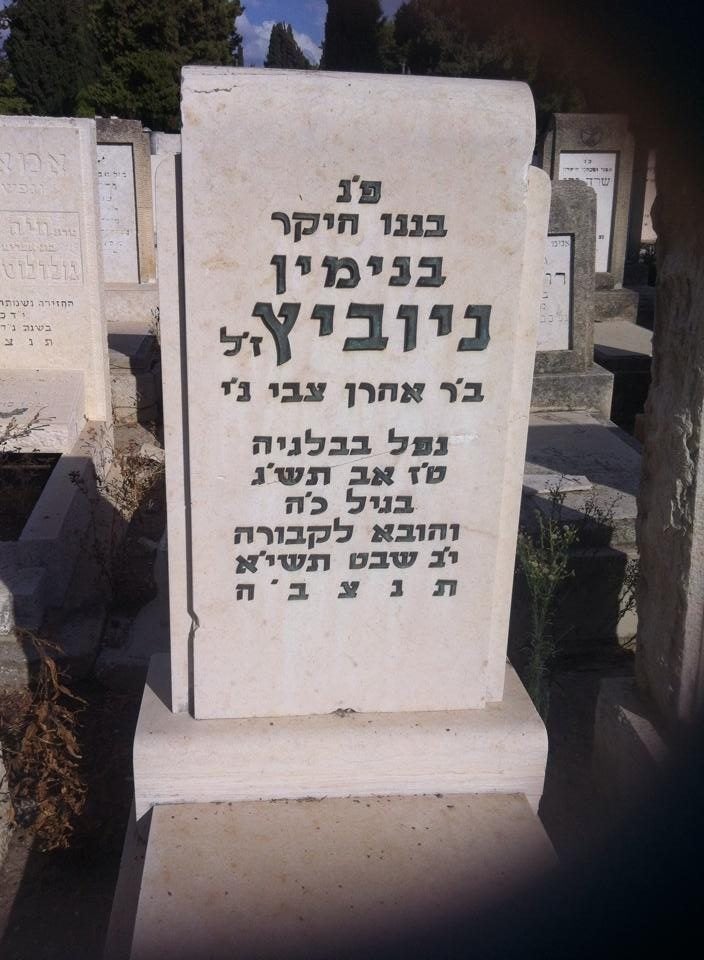

Buried at: Kiryat Shaul cemetery, Tel Aviv, Israel

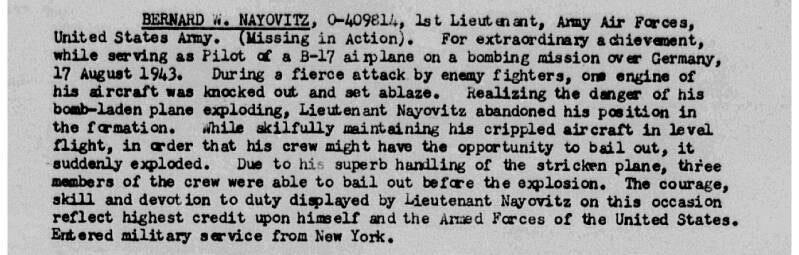

Picture: Barbara (McDonnell) Guzik Picture: Reuben Nayovitz

Final resting place of Bernard Nayovitz at Tel Aviv, Israel

Pictures from Gila (Druk) Arenson

Bernie Nayovitz sitting far left.

Photo Barbara (McDonnell) Guzik

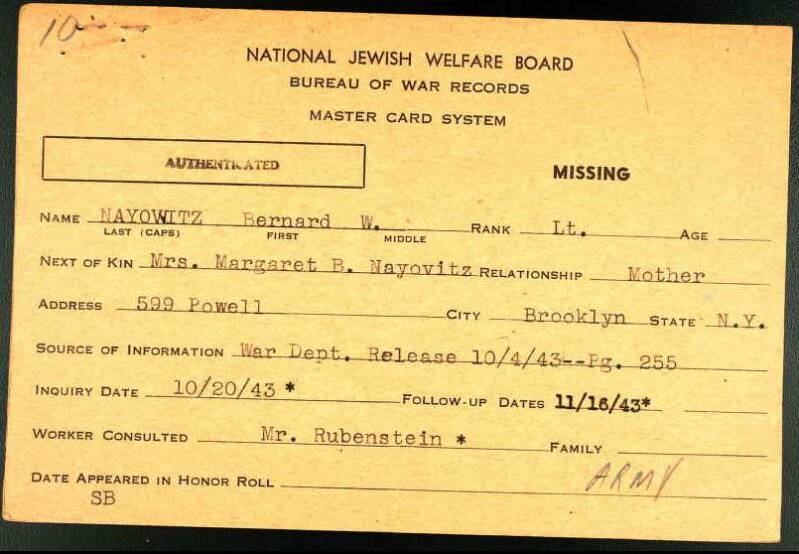

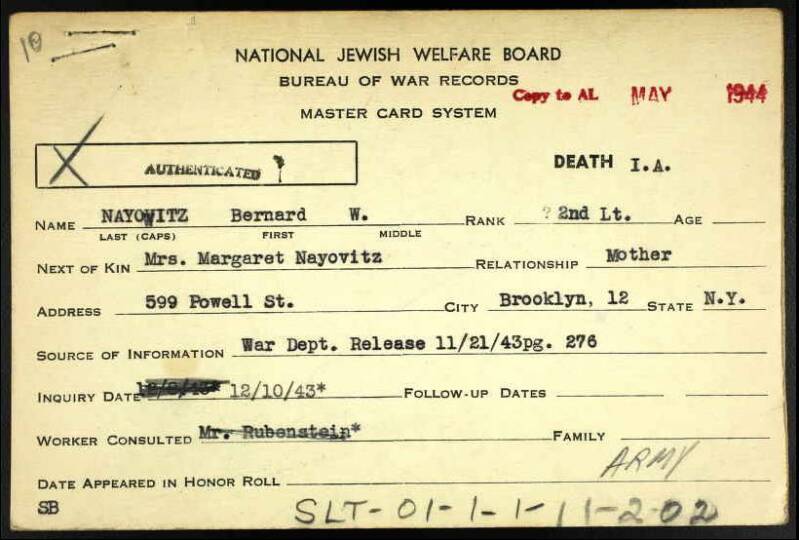

German document about the burial of Bernard

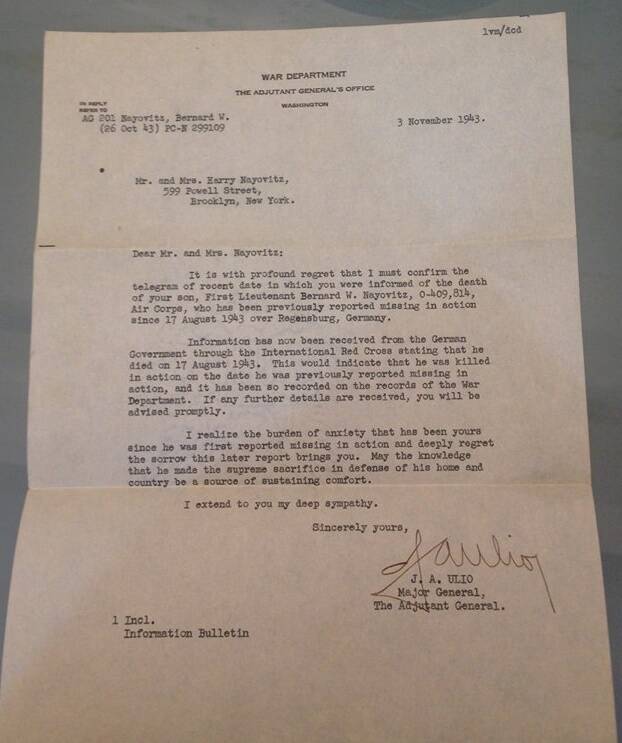

Letter sent to Bernard's parents confirming his death.

Letter sent to Bernard's mother.

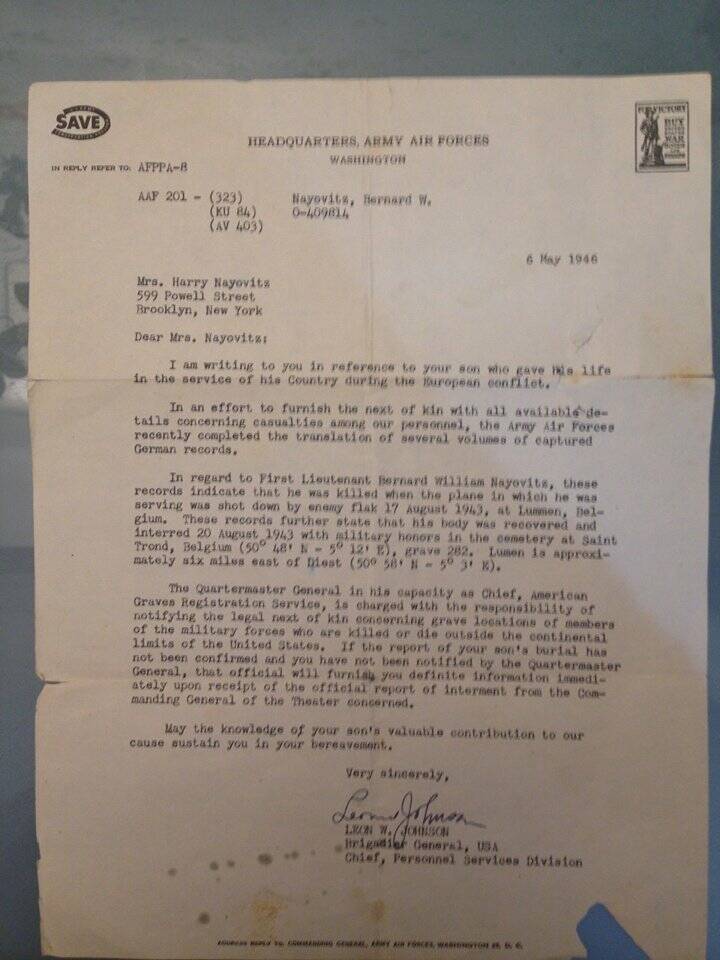

Bernard receives the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross)

Newspaper Brooklyn Eagle 21 November 1943

Escape kits signed by Bernie Nayowitz on 8 August 1943. This mission was cancelled.

(Doc. via Marc Benson)

Info from MACR:

Info: Marc Benson

Newspaper article 8 November 2013:

Written by Larry Yudelson in The Jewish Standard

http://jstandard.com/content/item/portraits_of_veterans/29011

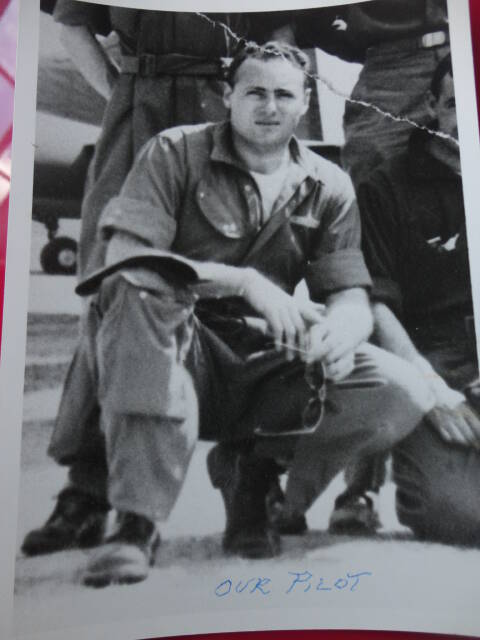

Joseph Nayowitz and his son Reuven pose with a portrait of their brother and uncle Bernie, who was shot down over Belgium in 1943.

If it weren’t for the war, Bernard Nayovitz would have been a vet.

He had the degree, from Texas A&M University. Veterinary medicine was not a profession commonly chosen by Jewish children born on the Lower East side to Yiddish- and Hungarian-speaking immigrant parents in the final months of the Great War, and raised in Brownsville, Brooklyn. But it made sense at Texas A&M, which had recruited him after seeing him play football for Tilden High.

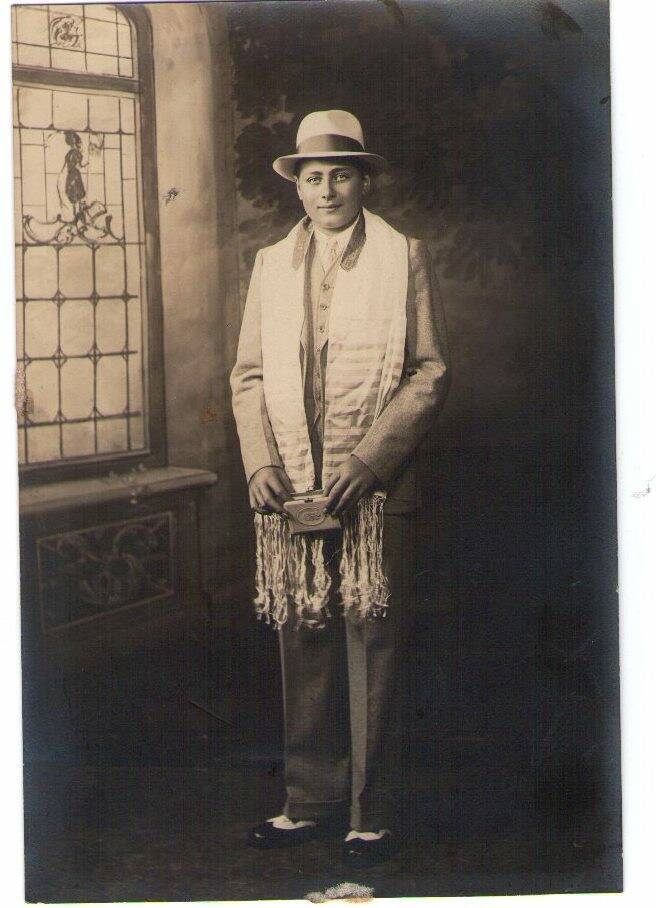

Bernie was big. In his bar mitzvah pictures, he already stands shoulder to shoulder with his parents.

His brother Joseph, three years younger, today a resident of Teaneck, remembers trying to chase after him in the park. He could never catch up, of course.

Bernie was named All American Fullback — until a dislocated shoulder ended his sports career. Sidelined, he lost his college scholarship. So he joined Reserve Officers Training Corps.

And when graduation day came, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant immediately.

In another century, the Army might have needed a freshly graduated veterinarian. Not in World War II. He chose the air force.

His brother remembers building and flying model airplanes made from balsa wood. “He was interested in them — but not more than most kids.”

After a six month pilots training course, he was assigned to fly a B-17.

The all-American Jewish flyer gave his plane a name that looked homeward back to Brownsville: “Dear Mom.”

Joseph remembers the last time he saw his older brother. He had come back for a supper visit before flying back overseas. He couldn’t say where he was going or how he was leaving: There was a war going on and loose lips could sink ships, whether in the sea or in the air.

“Look out the window,” Bernie said, knowingly.

And sure enough, after he said his goodbyes and left, they heard the sound of a low flying plane which tipped its wings as it flew by.

“Time flies by so quickly,” Joseph recalled this week. “It almost seems like something I studied in school instead of something I lived.”

It was August 1943 when the knock on the door came. Joseph had a premonition. He answered the door, and when he saw the uniformed officer, the designated bearer of bad news, he went out and closed the door behind him, to spare his parents, if only for a minute.

“Dear Mom” had been shot down somewhere over Europe and Bernie was dead, as were five others of the 10-man crew. Two soldiers had been taken captive; two more escaped.

For 20 years, their mother tried not to believe the news.

After the war, with secrecy lifted, the family learned that Bernie was buried near where his plane had crashed in Belgium.

The army offered to relocate his remains; he is buried now in Tel Aviv.

There was a third brother, Abraham, who also was a pilot. He too wanted to fly combat missions; the air force wouldn’t allow it. Instead, he flew transports, carrying troops and equipment, and staying far away from enemy fire. In the end, he logged far more flight hours than his older brother.

Reuven Nayowitz (only Bernie spelled the family name with a V), owner of Judaica House in Teaneck, had heard the stories of the uncle he never met, who died three years before he was born. He had seen the old pictures from the bar mitzvah, the picture of Bernie as a pilot to which a light touch of color had been added.

But all this abstract family memory was pushed aside by the sharp details of historical research in September. That’s when he heard from an informal group of amateur historians, most in Belgium, who were dedicated to documenting the crew of “Dear Mom.”

The effort started decades ago, back when the response to typed letters mailed to Washington were typed replies, divulging what was known about the plane’s crew. Now the group gathers on Facebook and used the internet to bring together far-flung researchers to piece together the story of “Dear Mom” and its doomed last mission.

And what they have found — between government records, and memorabilia held by the crewmembers’ families — is amazing.

There are photos of the crew. There is the sheet where Bernie signed out their emergency kits on August 10. That day’s flight was canceled; a week later, they took their kits with them.

And there are the reports written by the two soldiers who parachuted safely from the falling plane, and, aided by the Belgian resistance, made their way to North Africa.

At the beginning of the report are repeated warnings that all tales of escape are secret. Any clue as to how it was done might aid the enemy. Now, those wartime secrets are long since declassified.

“I saw tracers hitting the front part of our ship,” recounted Sergeant Beverly Geyer in his formal debriefing. “It must have hit our controls, for the plane fell over on one wing. We were heavily hit in the oil tanks. Oil and pieces of wing came flying by me. The navigator called and wanted to know what was popping. The pilot ordered us to bail out.”

And there are the details of the mission.

The B-17 that Bernie flew was known as “The Flying Fortress.” The Air Force had hoped that its defenses — including many machine guns — and its high altitude would let it fly safely through Nazi airspace. The reality was less kind to the pilots.

On August 17, 1943, “Dear Mom” was among 376 B-17s that took off from several bases in England in a daring daytime mission aimed at two industrial targets: The Messerschmitt fighter plane plant in Regensburg, and the ball-bearing factories of Schweinfurt.

“Dear Mom” was headed to Regensberg.

It was still 400 miles shy of its target when it was shot down.

It was the first of 15 planes that didn’t make it over the target; another 45 planes were downed before reaching their destination bases. This was the crew’s 14th mission. (A sense of the tension of life in those bomber crews was captured in the 1949 Gregory Peck film “Twelve O’Clock High.”)

August 17, 2013. Seventy years to the day, and a ceremony is held in Lummen, unveiling a monument to Nayovitz and his comrades. An American honor guard of young soldiers holds the American flag. In the audience: the amateur historians who had prodded the town to create the monument, and some family members of the crew. The Nayowitzes are not among them. Contact had not yet been made.

For Reuven Nayowitz, one of the most amazing things about this newly opened chapter of family history is how young his uncle was. True, Bernie was old for an enlistee — 25. But to Reuven, 70 years later, that seems terribly young to be flying a plane into combat.

“I have a son almost that age. He’s finishing up college,” Reuven says.

Pictures from Reuben Nayovitz:

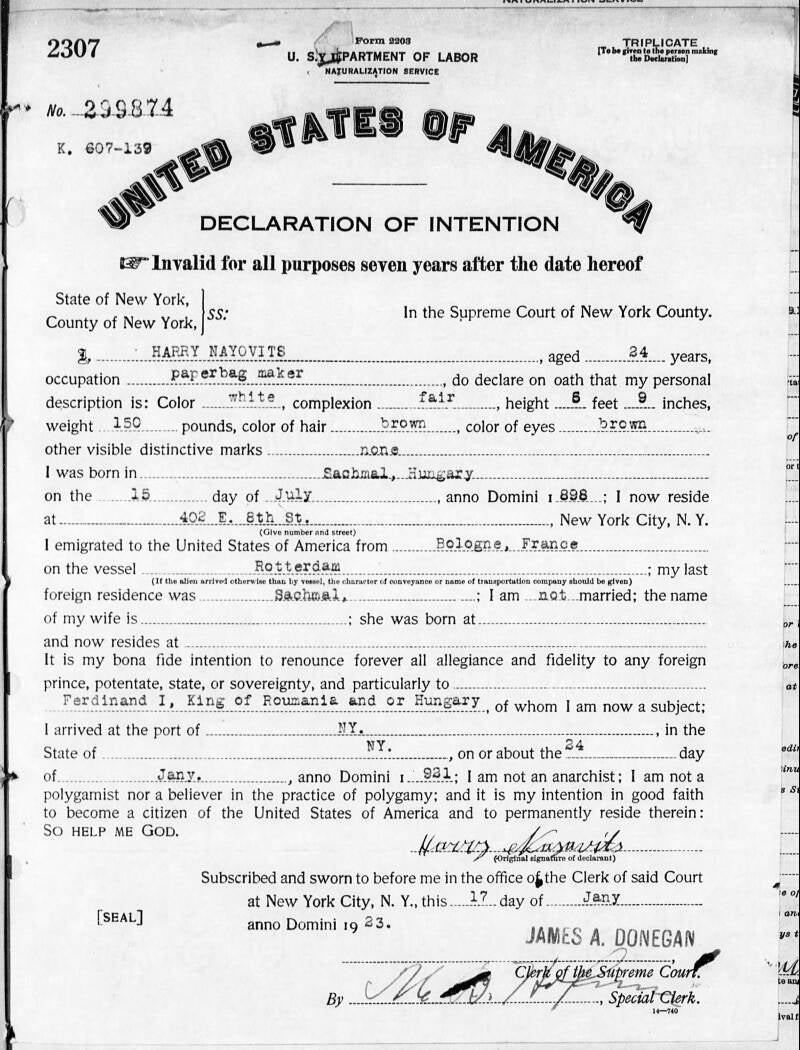

Parents Harry and Margaret Nayovitz emigrated from Hungary

Children from left to right: Bernard, Abraham and Joseph

Bernie's Bar Mitzvah 1930

Bernie in England May 14, 1943

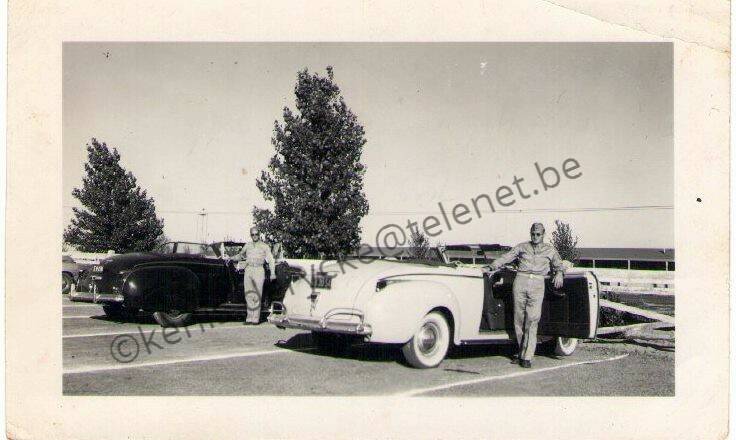

Bernie and his Dodge Thunderbird at Field Arizona 18 June 1942